There are many unknowns when it comes to neutrinos. Despite being the most abundant massive particle in the universe, the electron neutrino was discovered less than a century ago and it took until the year 2000 to discover the tau neutrino and we don’t even know how much it weighs!

Even less is known when it comes to cosmic neutrinos, but what we do know is that their energies go way beyond those from the Sun and Earth! While the processes that create neutrinos in the Sun can account for neutrinos up to the MeV-GeV range (1 million – 1 billion eV), we actually detect particles up to the PeV (10^15) energy level!

That’s an extraordinarily high amount of energy, and these ultra-high energy (UHE) neutrinos must clearly be made through different processes in some extremely-high energy environments! That leaves us with 2 questions: where are these sites, and how are these neutrinos made?

Let’s explore 2 main sources and one theory as to how they’re made.

Where are UHE neutrinos made?

There are 2 main sites that physicists think UHE neutrinos come from: Active galactic nuclei (AGN) and gamma-ray bursts (GRBs). It’s important to note that these are not the only hypothesized sources of cosmic neutrinos, but they seem to be the most popular sources in research papers.

Active Galactic Nuclei

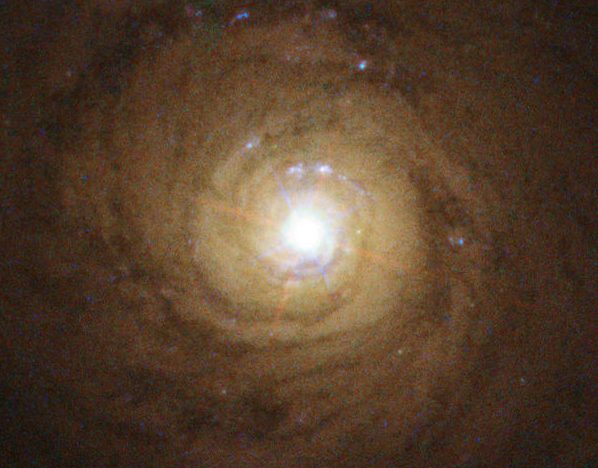

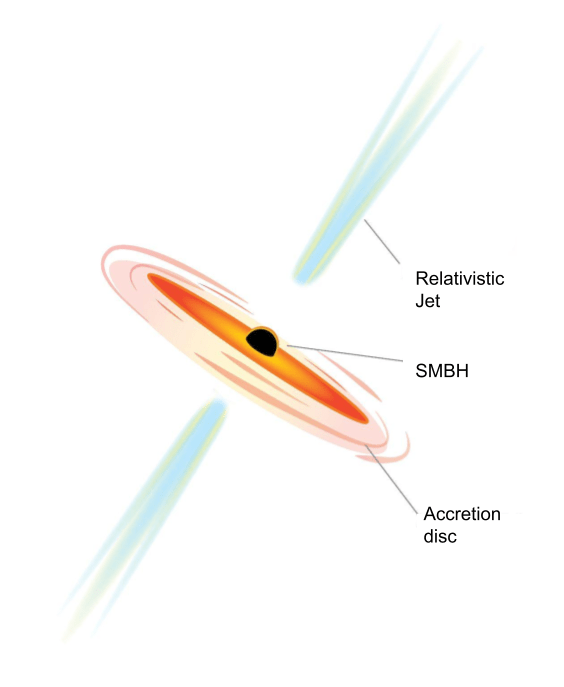

Active galactic nuclei (AGN) are early universe galaxies with extremely luminous cores, sometimes overpowering the stars in the galaxy such as in the case of quasars and blazars. There are 3 main parts of an AGN: The Supermassive black hole (SMBH), the accretion disc surrounding the SMBH, and sometimes there are 1 or 2 relativistic jets perpendicular to the disc’s plane.

There are numerous sub-types of AGN such as quasars, blazars and Seyfert galaxies. Quasars and blazars are the more powerful of the sub-types, and typically have extraordinarily high luminosities to the point where they look like nearby stars. Such a high energy environment should be the perfect place to look for cosmic neutrinos!

When it comes to where in AGN the neutrinos are made, we have a couple energetic avenues to explore. Firstly, the accretion disk is a highly magnetized site close to the SMBH and is also where stars get pulled apart in tidal disruption events (TDEs). This means the neutrinos could be made as a result of some interaction involving the magnetic field, or they could also be made in a TDE.

There is also the idea that the relativistic jet could be responsible for neutrinos, but we don’t know how jets work and so there aren’t many concrete findings regarding this, and my opinion may result in getting a chair flung at me next time I’m on campus!

Another proposed secondary site of creation (which I found particularly interesting) is the intracluster medium (ICM) surrounding AGN and galaxies! The reasoning behind this is that theoretical evidence suggests the AGN itself may not be able to produce the quantity of UHE neutrinos we expect, so there needs to be some second step. In this idea, Cosmic Rays that are produced in the AGN and channeled through the relativistic jet could interact with the ICM to produce the remaining neutrinos.

Gamma-Ray Bursts

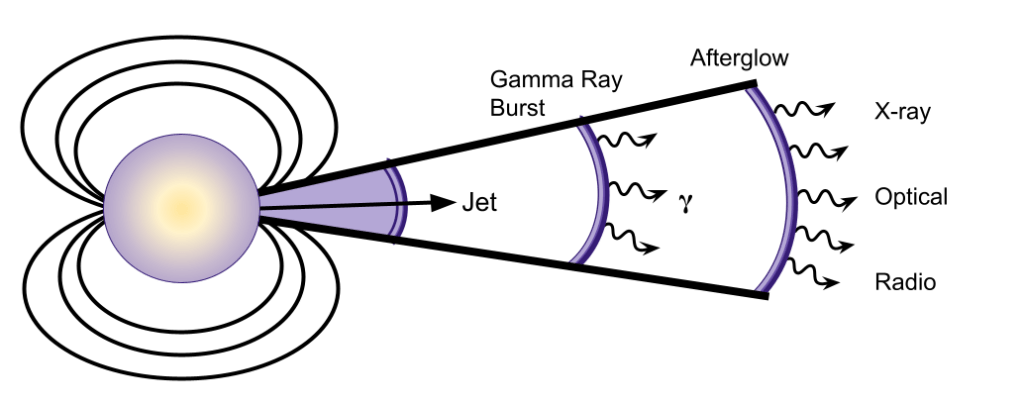

Gamma-ray bursts are extremely violent explosions that span across the entire electromagnetic spectrum and release unbelievably high amounts of energy. One particular burst, GRB 080319B, was visible to the naked eye for about 100s despite occurring over 7 billion light years ago!

It’s remarkably difficult to pinpoint exactly what GRBs are and how they are made. This makes it even harder to then discuss how neutrinos are made in these events, but we do have some ideas to build upon.

Let’s first discuss what makes GRBs. If we plot a distribution of GRB duration such as the plot below from Ghisellini (2001), we can see two peaks with a bit of overlap. This suggests there are 2 ways to make a GRB, which we now know are binary neutron star or neutron star-black hole mergers in the case of the short-duration GRBs, and core-collapse supernova from the heaviest of stars being responsible for the long-duration GRBs.

where 90% of the total flux is detected. Taken from Ghisellini (2001).

This is somewhat helpful as we have 2 events to fit our theories and models to, which leaves less room for guesswork in a way. The main theory as to how GRBs are made is the Fireball Model. In this model, the merging or collapse produces a series of internal and external shocks which expand due to thermal pressure. The high energy bursts and gamma rays are created when these shock fronts interact, and material is also shot outward at relativistic speeds.

One problem with this idea is that it’s very thermal or hydrodynamic and there’s not much consideration for how magnetism may play a role which goes against some observations. Instead, some argue for a more magnetically-dominated model such as Poynting-Flux Dominated Jets. In this scenario, the emission is powered by magnetic energy in the ejecta. One example of this theory being more plausible is in GRB 080916C, which has very little to no evidence of a thermal component.

That being said, a lot of long-duration GRBs have plateaus in their light curves (see my post on supernova to learn more about why), which isn’t accounted for with Poynting-Flux Dominated Jets but definitely is with the Fireball Model.

How are UHE Neutrinos made?

The main idea for how UHE neutrinos are made is through matter (such as protons) interacting with background photons, which then results in a chain of decays leading to a UHE neutrino. What’s key is that the “parent” protons need to be at extremely high energy themselves if we are to obey the law of conservation of energy.

In all of the previous scenarios, there is some mechanism that accelerates material to relativistic speeds which gives these protons the high energies required. In the case of the AGN, the extremely magnetized accretion disk accelerates charged particles like the proton via synchrotron processes. In the GRBs, either the shock fronts or the magnetic field accelerate them.

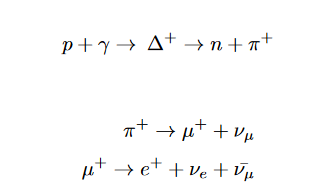

One the proton interacts with a photon, the proton should convert into a particle known as a Delta plus (symbol ∆+). This is a baryon with the same quark content as the proton, but a higher mass. The delta plus should then decay into pions, and then finally leptons including neutrinos.

This is an example of a photo-hadronic process. Some researchers also suggest that instead of the delta plus, the proton evolves into a Kaon which then decays into pions like the delta plus. An example chain of reactions with the delta plus is shown below:

First line: proton + photon (light) -> neutron + pion plus

Second line: pion plus (from previous line) -> anti-muon + mu neutrino

Third line: anti-muon (from previous line) -> positron (anti-electron) + electron neutrino + anti-mu neutrino

Observational Evidence

As of now (December 2023), there has only been evidence for a couple specific objects being neutrino sources. There have been no neutrino events associated with GRBs, but we do have a couple AGN that are linked to certain neutrino events that we can look at!

Our strongest neutrino source is likely a blazar called TXS 0506+056 (I’ll abbreviate it to just TXS from now on). A paper was released in 2018 by Padovani et al which analyzed both neutrino data and gamma-ray observations near TXS, and found that TXS was the most likely source of 2 neutrino events. They also found that the photon-neutrino spectra matched up with a mostly photo-hadronic model. A subsequent paper by Cerruti et al argued against the photo-hadronic processes and instead argued for a more lepto-hadronic framework.

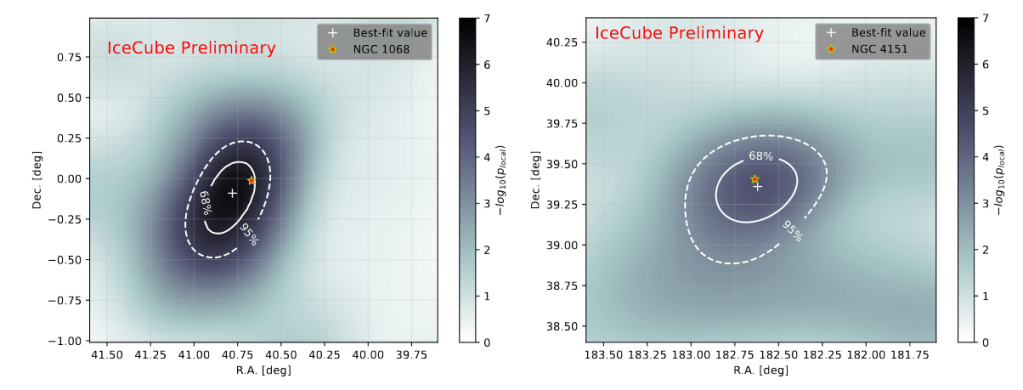

Other investigations such as those detailed in a paper by Goswami et al and Glauch et al found NGC 1068 (other names include M77 and the Squid Galaxy) and NGC 4151 (colloquially known as the “Eye-of-Sauron” Galaxy) to also have relatively high correlations with neutrino events.

(left) and NGC 4151 (right). The solid and dashed white lines represent 68% and the 95% confidence interval. Taken from Goswami et al (2023).

To summarise what we’ve covered, there are 2 main sources of neutrinos: AGN and GRBs. These are extremely violent and energetic parts of the universe that can produce particles of high energy, which is exactly what we need to make UHE neutrinos. The main process of neutrino production is likely photo-hadronic processes such as delta + and Kaon decay, and as of now there are only a handful of AGN linked to neutrinos. No GRB-neutrino associations have been found yet.

If you want to learn more, check out these:

Ghisellini, G., 2001, Gamma-ray bursts: Some facts and ideas.

Peterson, B. M., 1997, An Introduction to Active Galactic Nuclei. Cambridge University Press,

Murase, K., Stecker, F. W., 2022, High-energy neutrinos from active galactic nuclei,

These 3 papers looked at potential AGN sources of neutrinos:

Glauch, T., Kheirandish, A., Kontrimas, T., Liu, Q., Niederhausen, H., 2023, Searching for high-energy neutrino emission from seyfert galaxies in the northern sky with Icecube.

Goswami, S., 2023, Search for high-energy neutrino emission from hard x-ray agn with Icecube,

Padovani, P., Giommi, P., Resconi, E., Glauch, T., Arsioli, B., Sahakyan, N., Huber, M., 2018, Dissecting the region around IceCube-170922a: the blazar txs 0506+056 as the first cosmic neutrino source, MNRAS, 480(1):192–203

While I don’t want anyone throwing chairs at my favorite science blogger, the idea of scientific disagreements turning into Wrestle-mania style brawls is kind of amusing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can just imagine the Max-Planck Society installing a little cage for settling disputes when conversation isn’t working! Happy new year by the way!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! Same to you!

LikeLiked by 1 person