People are typically aware of 3 sizes of black holes: primordial, stellar, supermassive, and some people also recognize a new class called ultramassive black holes. We don’t really know how supermassive black holes form, and I won’t lie even stellar mass black holes can be quite a mystery!

I have actually talked about the types of black holes in a post 4 years ago, and did briefly mention ultramassive black holes. That was quite a while (and an undergraduate degree) ago, and my own knowledge on black holes has definitely improved since then. So today we’ll have a more deep dive into the largest of these black holes!

Today we’ll discuss supermassive and ultramassive black holes and why they’re somewhat baffling for astrophysicists.

Supermassive Black Holes

Supermassive black holes (SMBH) reside in the centre of all galaxies, with masses above 100’000 solar masses but most of them are millions to billions of solar masses.

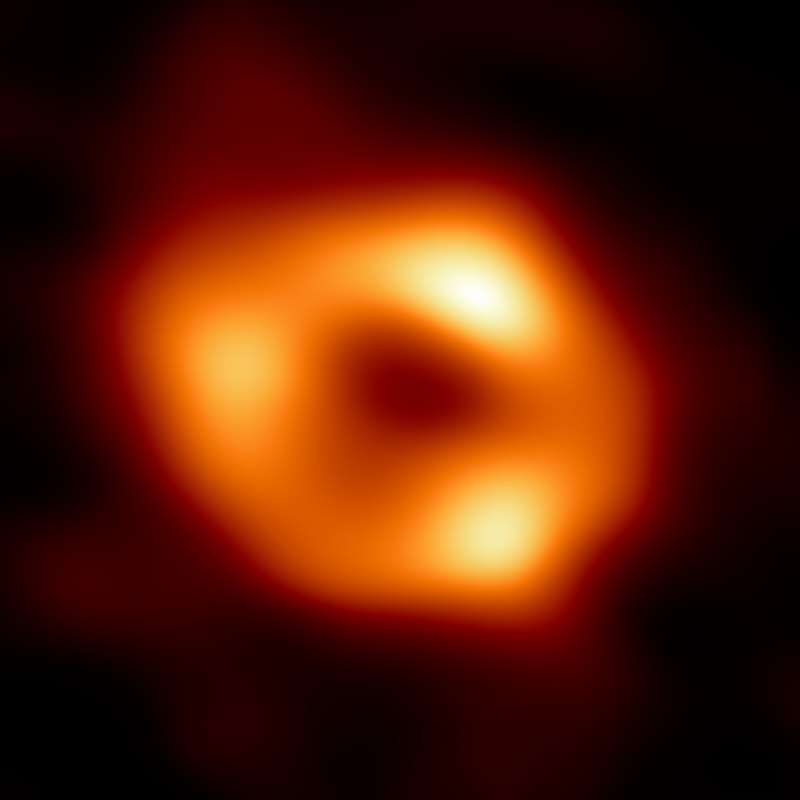

Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) is the SMBH inside our own galaxy, the Milky Way. It has a mass of around 4.3 million solar masses, and if we use the formula for the Schwarzschild radius we find that the SMBH is only around 25 million km in diameter which is smaller than the distance between the Sun and earth (149 million km).

Sgr A* is actually a relatively small SMBH. Andromeda, for example, doesn’t have a precise mass estimate yet but is expected to be around an order of magnitude more massive than Sgr A*. Andromeda’s satellite dwarf galaxy, M32, likely has a similar mass to Sgr A* at around 3 million solar masses.

To think that the Milky Way’s SMBH is comparable to a dwarf galaxy’s SMBH. That’s quite disappointing!

Ultramassive Black Holes

Ultramassive black holes (UMBH) are a subtype of SMBH which are tens of billions of solar masses. They’re essentially an elite club of most massive black holes observed so far. The term “UMBH” is actually not all that commonly used, although I’ve noticed it is recently picking up in usage in papers. Surprisingly “ultramassive” is most often used when talking about white dwarfs, which are not all that massive in comparison to a black hole!

You may be asking what mass do astrophysicists consider to be the border between SMBH and UMBH? There’s no agreed minimum mass for a UMBH, likely because the term just isn’t so commonly used yet. That being said, authors usually set their own definition when introducing the paper, which is often 10 billion solar masses.

TON618 is a great example of an UMBH, mainly because it is the most massive black hole observed so far! The most recent paper on TON 618 estimated its UMBH to be around 41 billion solar masses, although there have been older & higher estimates.

I’ve also seen some people say Phoenix A has the most massive UMBH, however I haven’t seen a paper that solidly backs this claim up. One of the only paper I found that included Phoenix A (under the name 2MASX J23444387-4243124) estimated the UMBH mass to be 19 billion solar masses, which is quite a bit smaller than TON 618!

How do SMBH and UMBH form?

That’s a good question, and one that researchers are actively studying. Our current knowledge of black holes is that they can grow slowly by accreting matter from an accretion disk, or alternatively they can rapidly grow through merging with other black holes.

The general consensus is that SMBH are likely stellar mass black holes that have grown through some combination of accretion and merging. The conditions for this growth are still very much a big unknown, and it does draw attention to the gap between stellar black hole masses (up to around 100 solar masses) and SMBH masses (over 100’000 solar masses). If SMBH do indeed grow from stellar black holes, we should see some intermediate “missing link” black holes in the process of growing, in which we have observed a fair few but not enough to come to any solid conclusions yet!

The transition between SMBH and UMBH is merely a case of the black hole accreting mass until it exceeds 10 billion solar masses. The class boundary is more so arbitrary than based on any black hole features.

That being said, SMBH slow down considerably in accretion rate when their mass gets to billions of solar masses. This is due to a few factors that need their own post explaining, but if we were to make a more informed split between SMBH and UMBH, this could be a useful property to consider.

References and Learn more:

The Blueshift Of Civ Broad Emission Line In QSOs by Xue Ge et al. This is where I got TON 618’s mass.

Bär et al (2019) included Phoenix A in a large scale analysis and estimated the SMBH mass to be 19 billion solar masses, which puts it much smaller than TON 618.

Accretion, growth of supermassive black holes, and feedback in galaxy mergers by Li-Xin Li.

TON618 NED data.

More info on UMBH and the merging of black holes.

This paper by Tang et al has a great intro on intermediate black holes.