When it comes to galaxy clusters, our main attention is usually focused on the galaxies and the stars inside them. What we don’t pay much mind to is the diffuse light between these galaxies, but in my opinion it’s just as important!

Today let’s explore a rather unique and newly emerging area of astrophysics. We’ll be looking at the importance of the light between galaxies may play in mapping out dark matter.

The Galaxy Cluster Environment

Let’s start off by looking at what’s going on in the galaxies. With the exception of elliptical galaxies, stars will orbit around in a fairly flat disk (ignoring any warps caused by collisions and interactions). The central supermassive black hole (SMBH) may be billions of times larger than the typical stars, but it isn’t the dominant mass in the galaxy and we can’t simplify things down to just consider the SMBH. Instead we also need to consider all the stars enclosed within an orbit too. Yes, they’re much smaller than the central black hole, but they do all add up!

This is important for the motion of a star in a galaxy, because more enclosed mass means the star orbits faster. However if the star is further away from the centre of the galaxy it’ll orbit slower.

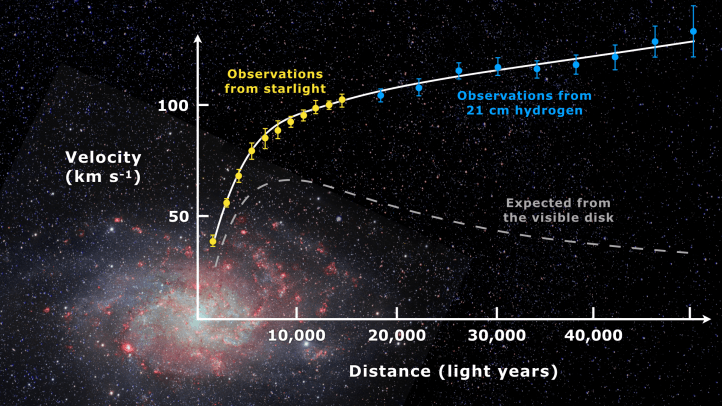

The edge of galaxies are much less populated than the centre, so we should expect stars to follow the plot below. The grey dashed line is what we expect given the maths and the number of stars we see, and the white solid line with data points is what’s observed. The difference between these lines is usually attributed to dark matter, but the main takeaway here is that there is an orderly rotation curve which stars follow which creates the galactic disk.

This doesn’t happen on the scale of galaxy clusters, which are groups of galaxies bound together gravitationally. Galaxies move around randomly like a swarm of bees. There is no disk-like analogue here. In terms of the dark matter structure, it appears that a galaxy may share a bigger common halo with a neighbour, which is then shelled within even larger halos, as inferred from gravitational lensing. This hierarchical structure and seemingly random motion of the galaxies makes it really difficult to simulate or research cluster motion, but that has made them quite an active and hot area of research!

The Intracluster Light

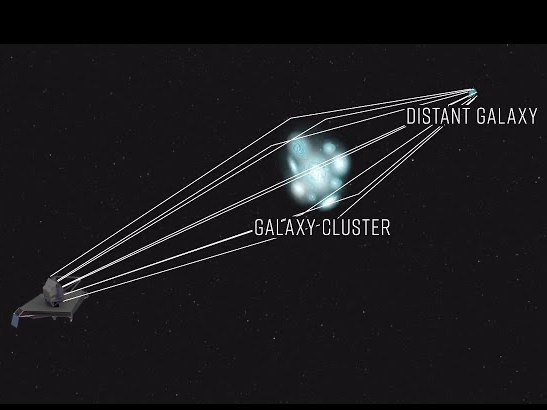

The main technique we currently use to infer the location and amount of dark matter is gravitational lensing. Heavy objects like galaxy clusters bend and distort light around them, with the level of distortion telling us how much mass there is. Lensing shows us that clusters are much heavier than they look. Galaxies and stars make up less than 5% (i’ve seen 1% being thrown around too) of the total mass of a cluster, and dark matter can make anywhere around 80-90% of the mass. You may have noticed that that doesn’t add up to 100%.

The missing mass is from the intracluster medium (not to be confused with the interstellar medium). The Intracluster medium (ICM) makes up the majority of baryonic (non-dark) matter in a galaxy cluster, but it’s actually in between the galaxies. The ICM is mostly hot and ionized hydrogen and helium plasma that is best viewed in the X-ray. It’s also made up of regular stars which have been ejected from a host galaxy. These stars create the very moody and dim light in the ICM, which is known as intracluster light or ICL.

Now what’s all this got to do with dark matter? Well these stars, rather than being bound in a galaxy and orbiting around a supermassive black hole in a disk, are instead just bound to the cluster as a whole and we can treat them as lone stars that move according to the gravity of the general cluster. Dark matter also does this, thus the ICL should be in the same places as the dark matter, both obey gravity so they should stick together.

In a way, it’s a bit like how bats use echolocation. Bats can’t see well and the dark doesn’t help with that, but they indirectly map out the area with sound and the time it takes to echo. We’re kind of indirectly mapping out the mass using starlight!

Evidence for this working

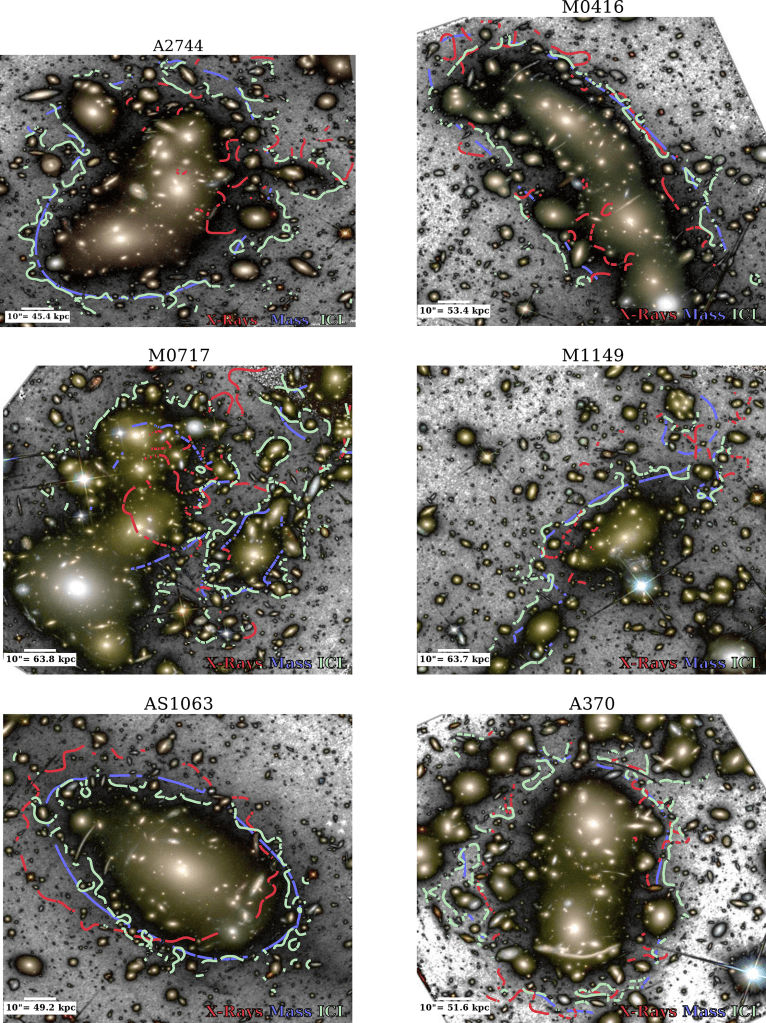

One of the first papers I read about the ICL and dark matter was by Montes and Trujillo all the way back in 2017, where they noted a close match between the ICL and the dark matter halos. The following year, they released this paper that goes into great detail on the subject. They looked at how well the ICL light traces out dark matter and, in general, the mass distribution of six clusters (from the Frontier Fields database) as determined through X-rays and gravitational lensing. They concluded that the ICL loosely matched dark matter distributions for the clusters, with some key figures from the paper below.

You can see that the outlines match up somewhat closely, but bear in mind that all techniques (ICL tracing, lensing and X-ray tracing) all have notable errors which need accounting for.

Montes and Tujillo have done a considerable amount of work beyond this paper that I don’t have time to go through today, but more recently Diego et al have looked at a cluster SMACS0723 (the first cluster) observed using JWST! They found at large distances from the centre of the cluster, the ICL doesn’t really match the visible mass distribution well, and hence their finding points towards a need for dark matter.

Overall, it’s looking pretty positive for the ICL as a useful tool! The three papers I’ve talked about are linked above, but I I highly recommend reading The intracluster light and its role in galaxy evolution in clusters by Miera Montes because it has a fantastic explanation of the ICL’s history, evolution, dynamics etc and it has a long list of references for even further reading! It’s quite fantastic to see how fast this field of dark matter physics has grown in the past 15 years!

Fingers crossed, hoping we finally figure out what the heck dark matter actually is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree. We don’t even know what kind of shape the dark matter halo is in the Milky Way, so we’ve got a long way to go!

LikeLiked by 1 person