I’d argue that one of the most mysterious parts of the Milky Way (and many other spiral galaxies) is the bar and how it works. It’s only very recently in the relative history of astronomy that we’re able to say with confidence that the Milky Way has its own bar!

But it is quite odd that bars exist in the first place. Gravity prefers spherical structures, so why do some disk galaxies have a weird rectangular structure in the middle? Today we’ll have a look into research around the Milky Way’s bar and how bars evolve over time.

Bar Basics

There are 3 main parts of the Milky Way: the bulge in the centre, the disk which is where most of the stellar mass is and (in my opinion) is where the fun happens, and the halo which is a near spherical shape made up of stars and dark matter that encloses the disk and bulge. We won’t be talking about the latter two today, we’ll only be focusing only on the inner parts of the galaxy.

You might not know this but most bulges in disk galaxies take on a bar-like shape, so they’re very common and clearly very important to consider when learning about galaxy evolution!

The Milky Way’s centre is very well-characterised as a mix of a peanut-shaped or boxy bar (in papers you will see this abbreviated to B/P), and it’s length is estimated to be between 3.5 to 5 kpc.

Bars tend to look a little yellow compared to spiral arms. Star formation doesn’t really happen in the bar, the only places that have a high star formation rate are the tips of the bar. That’s where you get a bit more compression of gas, some of which will collapse into stars. So overall a bar will be populated by mostly older stars, which are usually more yellow and red compared to big and young blue stars.

On the topic of bar tips, you might notice a small proportion of them also have very odd handle-like structures at their ends. They are referred to in literature as “Ansae-type bars” and are usually more common in the yellower early-type spiral galaxies, but in general they’re very understudied so their mechanisms for formation aren’t known well.

Also spectroscopic surveys show that there’s a lot of chemical diversity in the bar and quite a few different subgroups of stars. You also get a lot of variation in the kinematics, a recent paper by Han et al proposes that there are 3 subgroups (inner bulge, central bulge, and visitors from the halo) which can be fairly well split by either the eccentricities in the vertical height or by metallicity. In general, there’s a way to split bulge stars depending on what you’re focusing on, metal-rich, metal-poor, red clumps, RR lyrae etc. It’s a very cosmopolitan place!

Bar Kinematics

Now that we have a basic understanding of what the bar is made of material-wise and its shape, what is the bar made up of? How do stars get those weird orbits that create a peanut or box?

Thankfully, we do have some answers! There are a few “families” of orbits that support the bar, the biggest contributor being the x1 family. These are lemon-shaped orbits that look like circles that have been pinched at two ends.

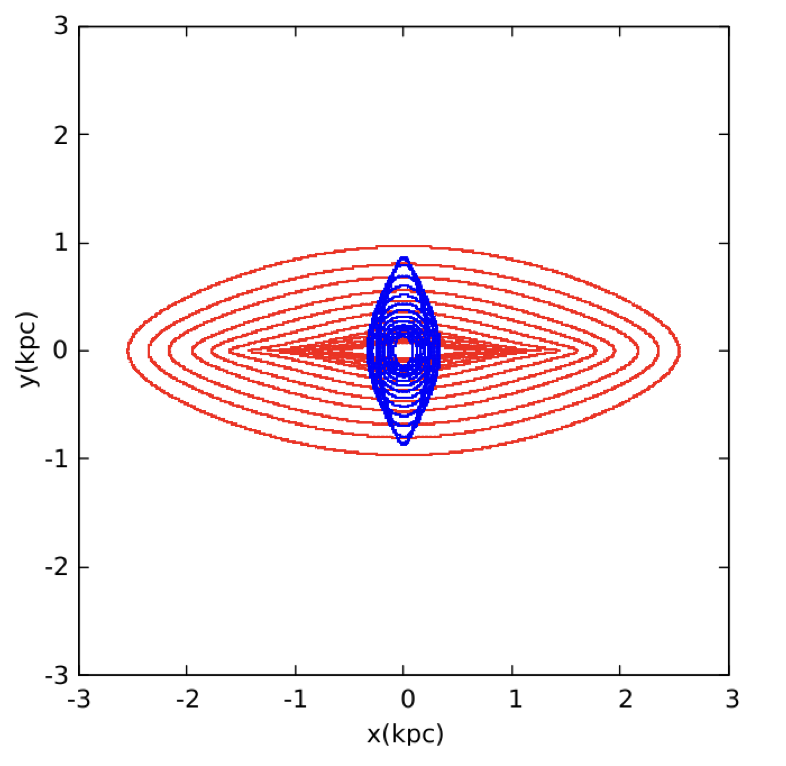

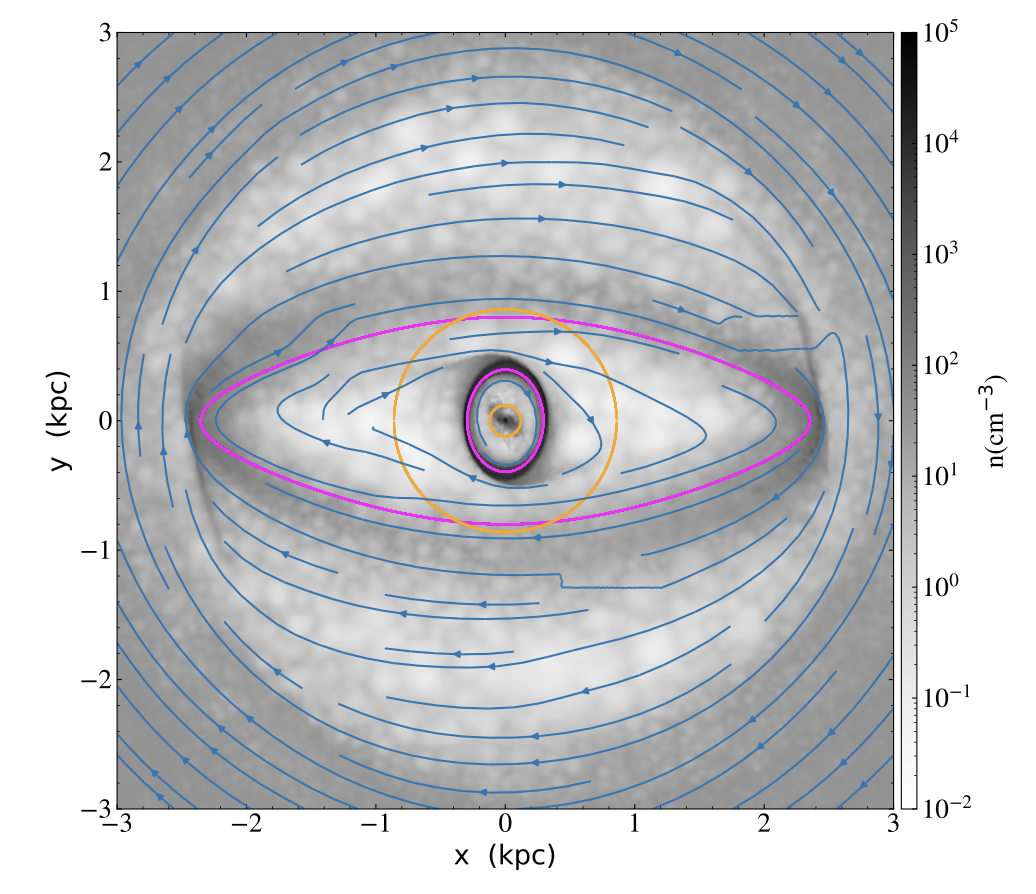

It’s actually difficult to get access to papers on these orbits online, but I read a paper a few months ago by Chaves-Velasquez et al that was focused on simulating the central molecular zone and the x2 family, but in this simulation they naturally include the x1 family! on the left image, the x1 are the red orbits, and on the right it’s the magenta.

The most likely cause of these orbits is some small instability early on in the development in a galaxy that triggers bar formation, for example a non-even density in the disk and bulge. If you change the density in a disk, you are redistributing the mass a little, but that can greatly affect the gravitational potential of a disk over time. Hence, over the course of a few billion years you can guide stars into these odd orbits which have a stabilising effect on the bar.

I think we should informally call the x1 orbits “lemon” orbits, mainly because we have another odd orbit to talk about which are banana orbits, and deviating from the fruit names we also have pretzel orbits!

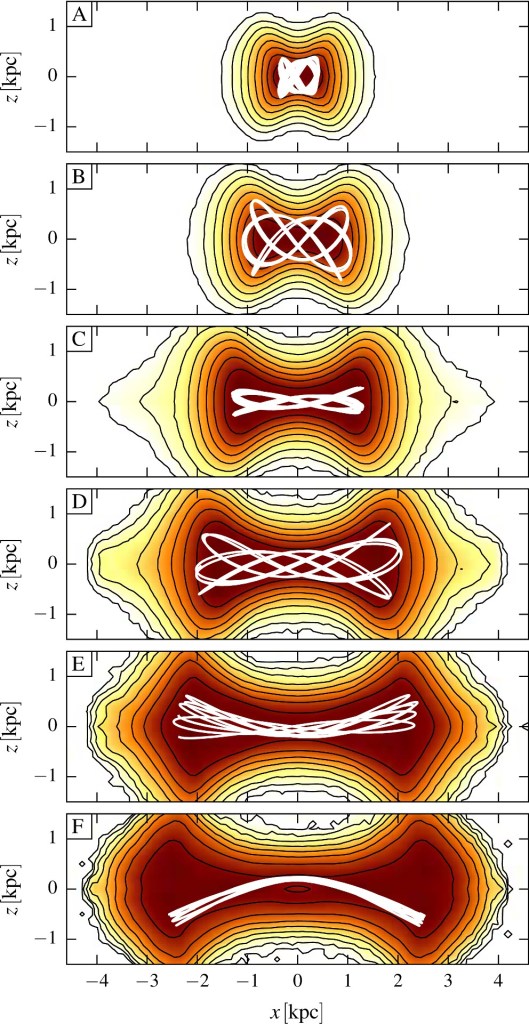

These are very important not necessarily for supporting the bar, but to thicken it out into the peanut or boxy shape. It’s quite difficult to observe individual orbits of stars in a galaxy including our own, so we rely on simulations to show us more finer detail. I recommend this paper by Portail, Wegg & Gerhard called Peanuts, brezels and bananas: food for thought on the orbital structure of the Galactic bulge which is a short read and has great figures showing the orbits.

The bottom plot on the right labelled “F” is an example of a banana orbit, and the middle plot labelled “D” is a pretzel orbit.

They found that you could effectively model the bar as a superposition of several “peanuts” produced by various orbits. In the general literature, we expect that most of these orbits would be banana orbits, which lift up from the galactic plane due to vertical resonances. And this would widen out the ends more than the centre, hence creating a 3d peanut shape that’s a little shaven off at the sides. BUT Portail et al actually show that a bigger portion of these actually have to be shaped like pretzels. It’s very much a question of to what proportion the bar is boxy compared to peanut. And if the bar is more X shaped or boxy than we thought, which is supported by recent literature, then the pretzels would play a bigger role.

Why Are Bars Useful?

So why do we even care about the bar, if it’s so central and very far away from the outer disk where all the fun happens?

Well just because it’s far away doesn’t mean its influence is negligible. The bulge and disk of a galaxy are in direct communication with each other, changes in the bar’s properties does eventually influence the outermost regions of the galaxy. For example, bars are vital for transfer of angular momentum and gas flow between the disk and the bulge, it can play a big role in reshaping the disk. Furthermore, a vertical strong bar can induce spirals in a galaxy, because they can serve as a non-axisymmetric perturbation.

What Don’t we Know?

But there are many unknowns regarding the bar in our own galaxy.

Firstly, it is expected that stellar bars rotate rigidly with an angular frequency/pattern speed which should gradually decrease over time. So the bar looks like it rotates as one big thing, and that should slow down over billions of years. A good estimate pattern speed opens up greater exploration into the kinematics of the galaxy, we’d be able to find resonances which in turn lets us explore the bars effects on the greater stellar population such as its role in the metallically distribution.

While important, the pattern speed is rather difficult to estimate from a purely observational perspective for both the Milky Way and other barred spirals due to the large timescales involved. Pattern speed estimates for the Milky Way range greatly between 31.5 and 44 km/s/kpc with the inclusion of statistical errors, however there could be up to 10 km/s/kpc of systematic error unaccounted for due to a bias from having half the galaxy obscured.

The pattern speed is also important because it carries information on the relative size the bar. High pattern speeds suggest the bar is moving quickly but is short, whereas lower ones indicate a slow long bar. And we don’t know that very well in the Milky Way.

Conclusion

Bars are a sign of a highly structured and evolved galaxy, they’re important for angular momentum transfer and gas flow between the bulge and disk. They’re supported by various oddly shaped orbit such as the x1 family, banana and pretzel orbits, all of which come together to create a peanut-boxy shaped bar.

That being said, we have a couple unknowns, mainly how fast the bar is rotating and proportionally how big it is. With improvements to the data we collect near the centre of the Milky Way and improvements to our simulations of cold disks with self gravity, we should be able to narrow things down soon!

Resources & Further Reading

Here are some very useful resources for more information, I highly recommend Ronald Buta’s online textbook on bars, which is also linked below.

https://ned.ipac.caltech.edu/level5/March14/Buta/Buta5.html

https://academic.oup.com/mnrasl/article/450/1/L66/986138

I also recommend if you want to look at a paper that focuses on simulating bars, this one has some interesting plots and results:

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2021arXiv211105466T/abstract

There used to be a bar near me called the Peanut Bar. It was in a boxy looking building. This should be enough to make me remember that our galaxy has a boxy/peanut bar at its center.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They owners were clearly up-to-date with the science!

LikeLiked by 1 person